After a little break were are happy to bring back our segment Breaking The Scene, where we dissect a pivoting scene from one of our featured short films with the help of the director. In this edition we get behind the mind of Robert Savage and expose the tantalizing rotating tunnel scene from his film ‘Dawn of the Deaf‘.

Warning: Spoiler alerts ahead – please watch the film below.

Watch Film

The film holds three completely different storylines that highlight the weaknesses, struggles and strengths of being deaf. Each story has its own little shocking moment, which one was your favorite?

Robert: I’m really happy with how all of the strands came together, and they all have moments that really define the film – the scene with Sam and her stepfather, the underpass scene, the lip-ripping finale. I’m really pleased that each strand has its own feel and tone, while still feeling like parts of the same whole – we shot each story chronologically, so it really felt like making three short films back-to-back.

But that’s not really answering your question – I think Sam’s storyline is the most deeply felt, because of how rooted we are in that character’s perspective. The other storylines are a little more tricksy and play with the audience’s perspective, but Sam’s timeline is very direct and emotive. I don’t have a favourite, but I think emotionally Sam’s storyline is the heart of the film.

The tunnel scene starts at about two thirds into the film, and up to this point there is absolutely no sign of anything zombi-ish going on. Tell us how this moment came about, how you decided to use a random couple argument to create the film’s big shocker moment?

Robert: I wanted to spend a lot of time for the audience to get to know the characters, empathise with them and understand a little bit about the different aspects of Deafness we were portraying – I always think that people underestimate Horror audiences, and their tolerance for character development and craft, and the film has played brilliantly at horror festivals around the world, despite a “slow” build up to the horror.

The idea was also to make the audience forget they were watching a horror at all, so that when the apocalypse arrives, they are as bewildered as the characters. The idea to have the “reveal” come out of a scene where two characters were arguing in sign language came from an experience I had on a tube – it was packed and thunderously loud, and right at the back were a Deaf couple arguing. They were totally immersed in their fight, and able to continue despite the noise, and I immediately pictured a scene in which the world ended while a Deaf couple were engrossed in an argument, none the wiser.

The cut off subtitles were frustratingly brilliant, it made us realize that the conversation here may not be all that important, that we should be looking for something out – yet keeps us ever so concentrated at trying to capture what’s said and blurring out the background. What was the true intent here? Was that something planned before hand, or just a cool idea that came about in post-production?

Robert: This came as part of a discussion with our Sign Language consultant Samuel Dore, a brilliant Deaf filmmaker in his own right, about how to shoot BSL (British Sign Language) — there is one school of thought which believes that BSL should be shot to always include the hands and face of the person signing, forgoing close-ups and cutaways. I chose a more conventional shooting style, but included that moment as a reference to filmmakers who shoot in a “sign-safe” style — when the audience cannot see hands and face, we deny them the subtitles.

In such a pivoting scene, the location can be such a key factor. Tell us about this particular spot, and what you feel it brought to the film?

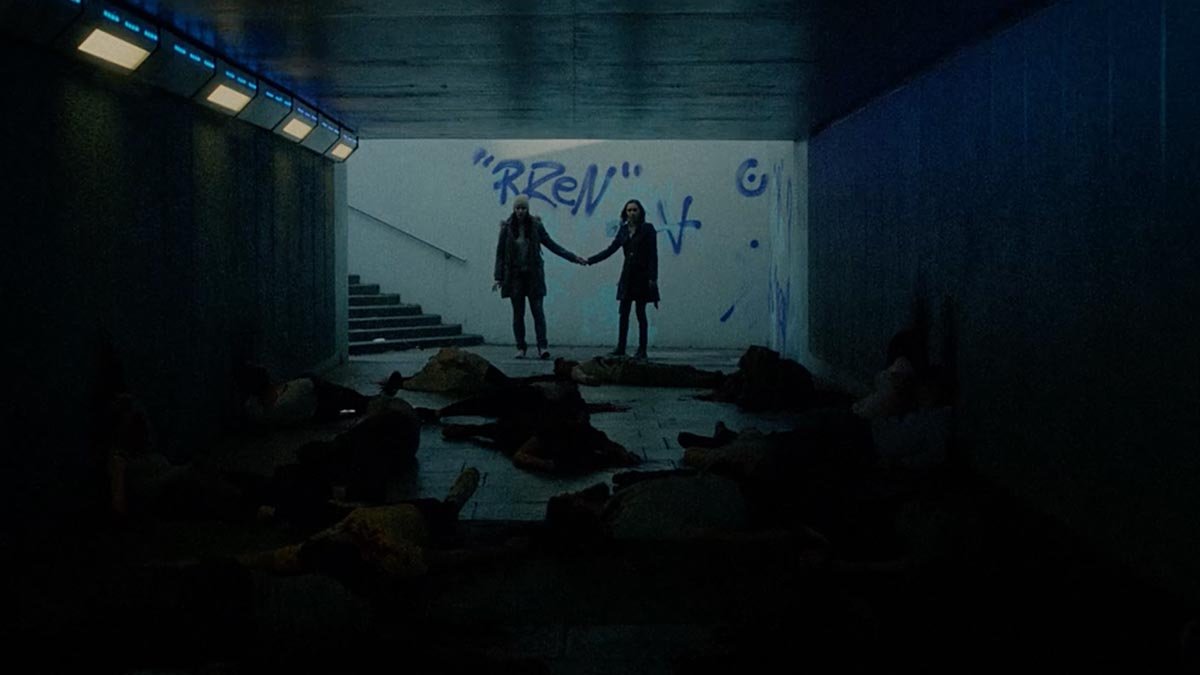

Robert: The appeal of the underpass was twofold – the main reason we shot there is because we had free access to it. The tunnel sits beneath the Waterloo roundabout in Central London, and would normally cost thousands of pounds to shoot in. However, I had a contact who was able to get us permission to shoot there for no cost. Secondly, I thought that by shooting in a tunnel and achieving the scene in one unbroken shot, we could suggest a scale of destruction that we could not afford: the camera begins up above, so that we see Waterloo Roundabout and all the hundreds of people milling about (not extras) and then we move into the tunnel, which we controlled and filled with 70 of our own extras. When the Pulse hits and we see the bodies, the audience also imagines all the people up above the tunnel are dead too, since we saw them at the start of the shot. This allowed us to give a sense of a world-wide (or at least City-wide) epidemic, but only actually showing a handful of bodies.

The obvious question: how did you manage to get splattered bodies on the ground so quickly?

Robert:The extras all had multiple layers on – a clean jacket over the top of a bloody shirt or something similar. As the final pull-back begins, the extras pulled off their top layer and lay into position as the camera tracked back. Meanwhile, make up artists ran around and applied blood, only a step behind the camera.

This is a fairly strongly choreographed scene, how many shots did it take to get it right?

Robert: We rehearsed the scene in a studio beforehand for a whole day and then when we arrived on location we rehearsed several more times with the camera, so that everyone was clear on the timings. We did 14 takes and used the very last one – it took a whole day to get right.

Now that the Zombie apocalypse is behind you, what’s next on the horizon for you? Any new projects you’d like to share?

Robert: We’re making a Dawn of the Deaf feature film, which I’m very excited about, and I’m also developing a couple of other features including an Amblin-style horror film and a time travel thriller. I’ve just finished up on my first TV show, for Channel 4, which is called “True Horror” – I wrote and directed an episode based on an amazing true story. I’m also in post on a new horror short called “Salt”, which I can’t wait to share before the year is out.